As with many citizen science programs, the value of the work cannot be measured in numbers alone.

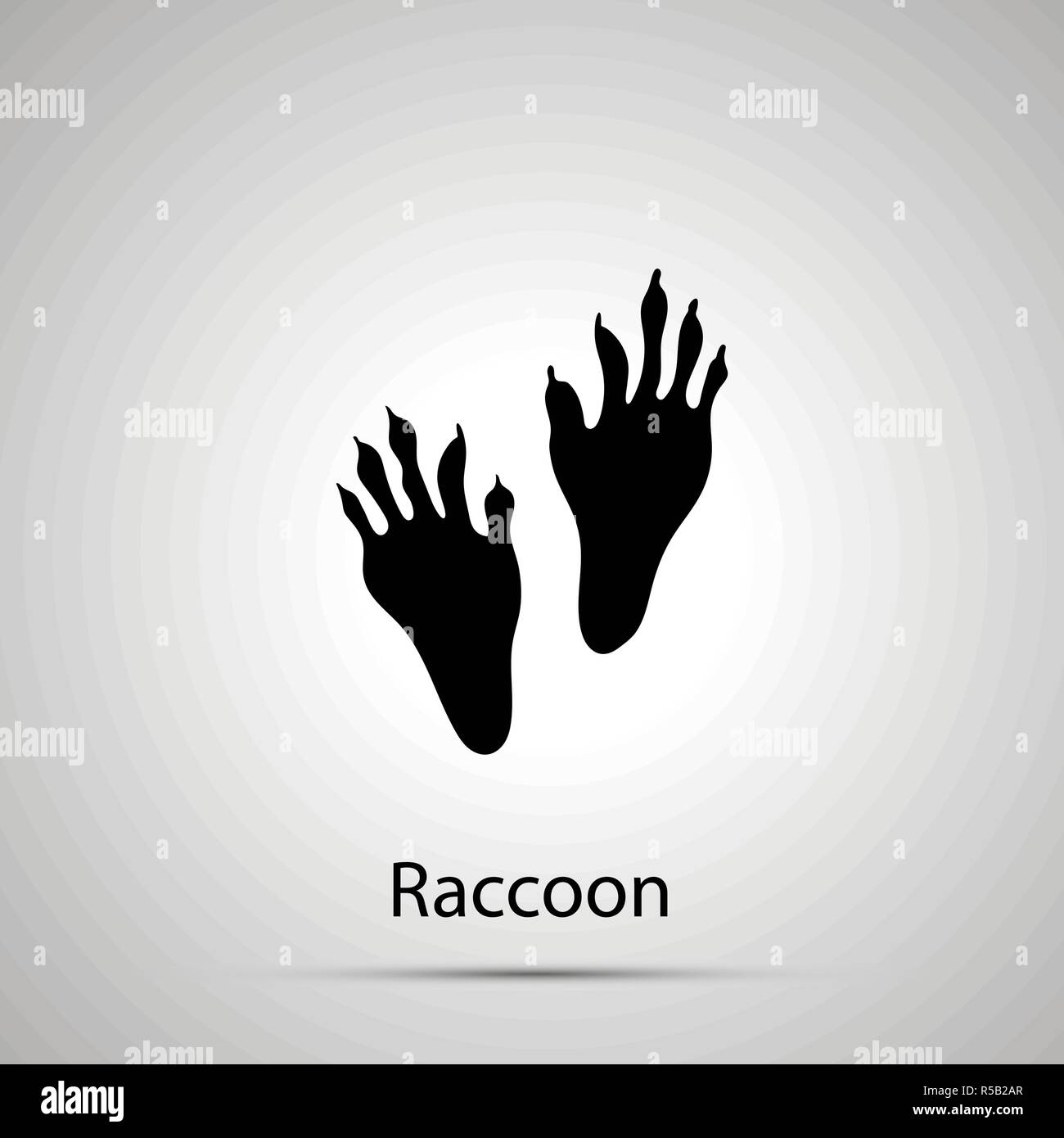

Meanwhile, resources like the iNaturalist project The North American Animal Tracking Database are being expanded and improved as important tools in the field. In Washington, the Cascades Citizen Wildlife Monitoring Project finished their ninth winter of combining snow tracking with year-round camera traps. Image of a mountain lion caught be a camera trap (Credit: Richard Mahler) Elsewhere, in California, the San Diego Tracking Team has a ten-year record of observations, with volunteers committing over 1500 hours per year to monitoring some 50 locations around San Diego County. Construction of the first overpass has just begun. Their data is regularly used in county development and state transportation plans and has helped win approval for three wildlife underpasses and three overpasses across highways near Tucson. They now monitor 50 1.5-mile long transects within 7 priority wildlife corridor areas and have conducted over 1,000 track count surveys, with over 4,000 records for more than 40 different animal species. In Arizona and southern New Mexico, Sky Island Alliance has been training volunteers since 2001. In this, the program is joining other citizen scientist tracking projects in the American West. A larger goal of Pathways is to help these agencies create wildlife corridors through which animals can move freely and safely through rural and urban communities. Using tracking teams to monitor specific transects, as well as camera “traps” that take pictures of animals in the wild, the program provides scientific data to local, state, and federal agencies. But citizen scientists across the country are learning the tracks and signs of wild animals for programs like Pathways: Wildlife Corridors of New Mexico, who has taken on the task of documenting the movements of six species-black bear, elk, mule deer, bobcat, pronghorn, and mountain lion-between the mountain ranges of northern New Mexico and their river valleys. The skill of identifying animal tracks may seem arcane-or at least relegated to hunters and game wardens. A track that resembles a human handprint but with pinpricks of claws in the dirt. Like a barefoot human footprint, with five toes, except that the big one is on the outside. There’s no mistaking, really, the roundness and size of this bobcat’s paw, the leading toe and absence of claw marks. You can admire them for long minutes, imagining the animal who made them. īy Sharman Apt Russel Wild animals glide so easily through the landscape, into bushes and leaves, up trees, around corners, even diving into the earth, so that you often wonder: was that a fox or a wish? Did I really just see a bobcat? Is that whoofing noise a black bear, startled now and galumphing down the hill? That’s the great thing about tracks. For more wildlife related citizen science projects, visit SciStarter. A citizen science program documents the movement of six species in the mountain ranges and river valleys of northern New Mexico helping create wildlife corridors.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)